the whole Scene from The Fiery Cross

“Do you want her?” I asked. I wasn’t sure whether I was hopeful of his answer, or fearful of it. The answer was a slight shrug.

“It’s a big house, Sassenach,” he said. “Big enough.”

“Hmm,” I said. Not a resounding declaration—and yet I knew it was commitment, no matter how casually expressed. He had acquired Fergus in a Paris brothel, on the basis of three minutes’ acquaintance, as a hired pickpocket. If he took this child, he would treat her as a daughter. Love her? No one could guarantee love—not he … and not I.

He had picked up my dubious tone of voice.

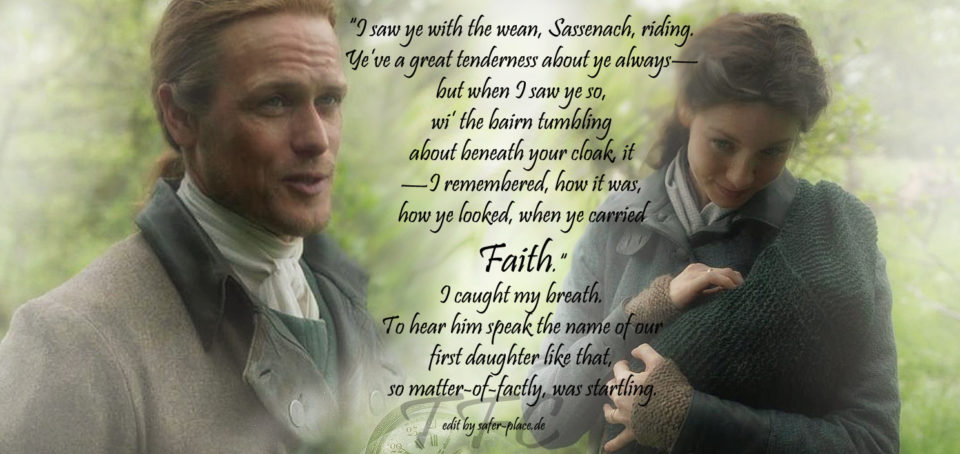

“I saw ye with the wean, Sassenach, riding. Ye’ve a great tenderness about ye always—but when I saw ye so, wi’ the bairn tumbling about beneath your cloak, it—I remembered, how it was, how ye looked, when ye carried Faith.”

I caught my breath. To hear him speak the name of our first daughter like that, so matter-of-factly, was startling. We spoke of her seldom; her death was so long in the past that sometimes it seemed unreal, and yet the wound of her loss had scarred both of us badly.

Faith herself was not unreal at all, though.

She was near me, whenever I touched a baby. And this child, this nameless orphan, so small and frail, with skin so translucent that the blue threads of her veins showed clear beneath—yes, the echoes of Faith were strong. Still, she wasn’t my child. Though she could be; that was what Jamie was saying.

Was she perhaps a gift to us? Or at least our responsibility?

“Do you think we ought to take her?” I asked cautiously. “I mean—what might happen to her if we don’t?”

Jamie snorted faintly, dropping his arm, and leaned back against the wall of the house. He wiped his nose, and tilted his head toward the faint rumble of voices that came through the chinked logs.

“She’d be well cared for, Sassenach. She’s in the way of being an heiress, ken.”

That aspect of the matter hadn’t occurred to me at all.

“Are you sure?” I said dubiously. “I mean, the Beardsleys are both gone, but as she’s illegitimate—”

He shook his head, interrupting me.

“Nay, she’s legitimate.”

“But she can’t be. No one realizes it yet except you and me, but her father—”

“Her father was Aaron Beardsley, so far as the law is concerned,” he informed me. “By English law, a child born in wedlock is the legal child—and heir—of the husband—even if it’s known for a fact that the mother committed adultery. And yon woman did say that Beardsley married her, no?”

It struck me that he was remarkably positive about this particular provision of English law. It also struck me—in time, thank God, before I said anything—exactly why he was positive.

William. His son, conceived in England, and so far as anyone in England knew—with the exception of Lord John Grey—presumably the ninth Earl of Ellesmere. Evidently, he legally was the ninth Earl, according to what Jamie was telling me, whether the eighth Earl had been his father or not. The law really was an ass, I thought.

“I see,” I said slowly. “So little Nameless will inherit all Beardsley’s property, even after they discover that he can’t have been her father. That’s … reassuring.”

His eyes met mine for a moment, then dropped.

“Aye,” he said quietly. “Reassuring.” There might have been a hint of bitterness in his voice, but if there was, it vanished without trace as he coughed and cleared his throat.

“So ye see,” he went on, matter-of-factly, “she’s in no danger of neglect. An Orphan Court would give Beardsley’s property—goats and all”—he added, with a faint grin—“to whomever is her guardian, to be used for her welfare.”

“And her guardians’,” I said, suddenly recalling the look Richard Brown had exchanged with his brother, when telling his wife the child would be “well cared for.” I rubbed my nose, which had gone numb at the tip.

“So the Browns would take her willingly, then.”

“Oh, aye,” he agreed. “They kent Beardsley; they’ll ken well enough how valuable she is. It would be a delicate matter to get her away from them, in fact—but if ye want the child, Sassenach, then ye’ll have her. I promise ye that.”

The whole discussion was giving me a very queer feeling. Something almost like panic, as though I were being pushed by some unseen hand toward the edge of a precipice. Whether that was a dangerous cliff or merely a foothold for a larger view remained to be seen.

I saw in memory the gentle curve of the baby’s skull, and the tissue-paper ears, small and perfect as shells, their soft pink whorls fading into an otherworldly tinge of blue.

All rights for the Picture from Outlander go to the rightful owner Starz/Sony

Quote and Excerpt by Diana Gabaldon from “The Fiery Cross”

I own nothing but the editing

Be First to Comment