From the Fiery Cross

Jamie was standing at the edge of the spring in nothing but his shirt.

I stopped dead, hidden by a scrubby growth of evergreens.

It wasn’t his state of undress that halted me, but rather something in the look of him. He looked tired, but that was only reasonable, since he had been up and gone so early.

The ragged breeks he wore for riding lay puddled on the ground nearby, his belt and its impedimenta neatly coiled beside them. My eye caught a dark blotch of color, half-hidden in the grass beyond; the blue and brown cloth of his hunting kilt. As I watched, he pulled the shirt over his head and dropped it, then knelt down naked by the spring and splashed water over his arms and face.

His clothes were mud-streaked from riding, but he wasn’t filthy, by any means. A simple hand-and-face wash would have sufficed, I thought—and could have been accomplished in much greater comfort by the kitchen hearth.

He stood up, though, and taking the small bucket from the edge of the spring, scooped up cold water and poured it deliberately over himself, closing his eyes and gritting his teeth as it streamed down his chest and legs. I could see his balls draw up tight against his body, looking for shelter as the icy water sluiced through the auburn bush of his pubic hair and dripped off his cock.

“Your grandfather has lost his bloody mind,” I whispered to Jemmy, who stirred and grimaced in his sleep, but took no note of ancestral idiosyncrasies.

I knew Jamie wasn’t totally impervious to cold; I could see him gasp and shudder from where I stood in the shelter of the rock, and I shivered in sympathy. A Highlander born and bred, he simply didn’t regard cold, hunger, or general discomfort as anything to take account of.

Even so, this seemed to be taking cleanliness to an extreme.

He took a deep, gasping breath, and poured water over himself a second time. When he bent to scoop up the third bucketful, it began to dawn on me what he was doing.

A surgeon scrubs before operating for the sake of cleanliness, of course, but that isn’t all there is to it. The ritual of soaping the hands, scrubbing the nails, rinsing the skin, repeated and repeated to the point of pain, is as much a mental activity as a physical one. The act of washing oneself in this obsessive way serves to focus the mind and prepare the spirit; one is washing away external preoccupation, sloughing petty distraction, just as surely as one scrubs away germs and dead skin.

I had done it often enough to recognize this particular ritual when I saw it. Jamie was not merely washing; he was cleansing himself, using the cold water not only as solvent but as mortification. He was preparing himself for something, and the notion made a small, cold trickle run down my own spine, chilly as the spring water.

Sure enough, after the third bucketful, he set it down and shook himself, droplets flying from the wet ends of his hair into the dry grass like a spatter of rain. No more than half-dry, he pulled the shirt back over his head, and turned to the west, where the sun lay low between the mountains. He stood still for a moment—very still.

The light streamed through the leafless trees, bright enough that from where I stood, I could see him now only in silhouette, light glowing through the damp linen of his shirt, the darkness of his body a shadow within. He stood with his head lifted, shoulders up, a man listening.

For what? I tried to still my own breathing, and pressed the baby’s capped head gently into my shoulder, to keep him from waking. I listened, too.

I could hear the sound of the woods, a constant soft sigh of needle and branch. There was little wind, and I could hear the water of the spring nearby, a muted rush past stone and root. I heard quite clearly the beating of my own heart, and Jemmy’s breath against my neck, and suddenly I felt afraid, as though the sounds were too loud, as though they might draw the attention of something dangerous to us.

I froze, not moving at all, trying not to breathe, and like a rabbit under a bush, to become part of the wood around me. Jemmy’s pulse beat blue, a tender vein across his temple, and I bent my head over him, to hide it.

Jamie said something aloud in Gaelic. It sounded like a challenge—or perhaps a greeting. The words seemed vaguely familiar—but there was no one there; the clearing was empty. The air felt suddenly colder, as though the light had dimmed; a cloud crossing the face of the sun, I thought, and looked up—but there were no clouds; the sky was clear. Jemmy moved suddenly in my arms, startled, and I clutched him tighter, willing him to make no sound.

Then the air stirred, the cold faded, and my sense of apprehension passed. Jamie hadn’t moved. Now the tension went out of him, and his shoulders relaxed. He moved just a little, and the setting sun lit his shirt in a nimbus of gold, and caught his hair in a blaze of sudden fire.

He took his dirk from its discarded sheath, and with no hesitation, drew the edge across the fingers of his right hand. I could see the thin dark line across his fingertips, and bit my lips. He waited a moment for the blood to well up, then shook his hand with a sudden hard flick of the wrist, so that droplets of blood flew from his fingers and struck the standing stone at the head of the pool.

He laid the dirk beneath the stone, and crossed himself with the blood-streaked fingers of his right hand. He knelt then, very slowly, and bowed his head over folded hands.

I’d seen him pray now and then, of course, but always in public, or at least with the knowledge that I was there. Now he plainly thought himself alone, and to watch him kneeling so, stained with blood and his soul given over, made me feel that I spied on an act more private than any intimacy of the body. I would have moved or spoken, and yet to interrupt seemed a sort of desecration. I kept silent, but found I was no longer a spectator; my own mind had turned to prayer unintended.Oh, Lord, the words formed themselves in my mind, without conscious thought, I commend to you the soul of your servant James. Help him, please. And dimly thought, but help him with what? Then he crossed himself, and rose, and time started again, without my having noticed it had stopped.

.…some time later…

“Was it God you were calling on to help you? When I saw you earlier?”

“Och, no,” he said. He looked away for a second, then met my eyes with a sudden queer glance. “I was calling Dougal MacKenzie.”

I felt a deep and sudden qualm go through me. Dougal was long dead; he had died in Jamie’s arms on the eve of Culloden—died with Jamie’s dirk in his throat. I swallowed, and my eyes flicked involuntarily to the knife at his belt.

“I made my peace wi’ Dougal long ago,” he said softly, seeing the direction of my glance. He touched the hilt of the knife, with its knurl of gold, that had once been Hector Cameron’s. “He was a chieftain, Dougal. He will know that I did then as I must—for my men, for you—and that I will do it now again.”

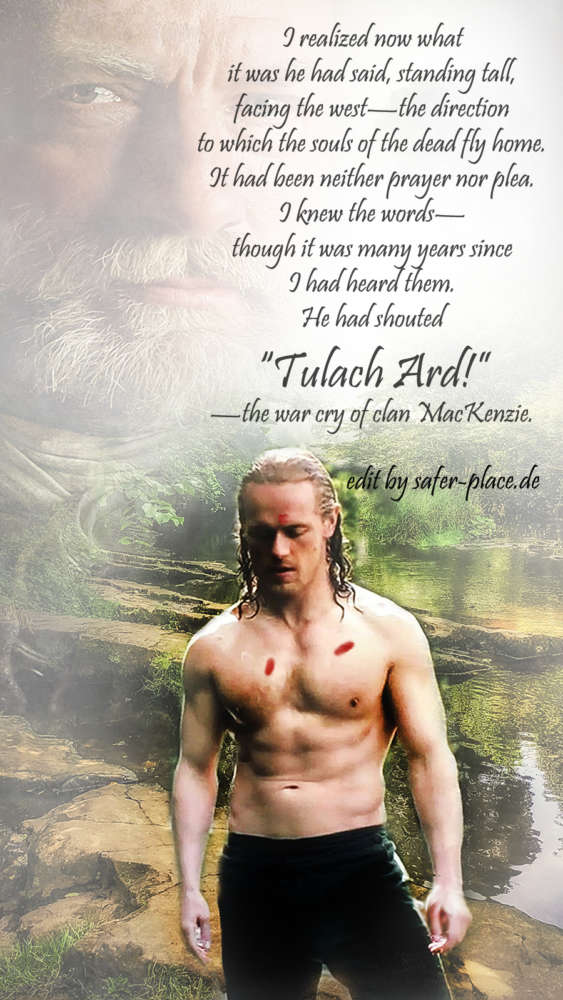

I realized now what it was he had said, standing tall, facing the west—the direction to which the souls of the dead fly home. It had been neither prayer nor plea. I knew the words—though it was many years since I had heard them. He had shouted “Tulach Ard!”—the war cry of clan MacKenzie.

All rights for the Picture from Outlander go to the rightful owner Starz/Sony

Quote and Excerpt by Diana Gabaldon from “TFC”

I own nothing but the editing

All rights for the Picture from Outlander go to the rightful owner Starz/Sony

Quote and Excerpt by Diana Gabaldon from “The Fiery Cross”

I own nothing but the editing

He looks younger in that photo than in the first year. Like a surfer kid on the beach. I wish I never age!

Beautiful! Such a wonderful passage!

it is…cant wait to see the whole scene on screen…